Public Life During Social Distancing: Two Perspectives in Montreal, the Southernmost Northern City [1]

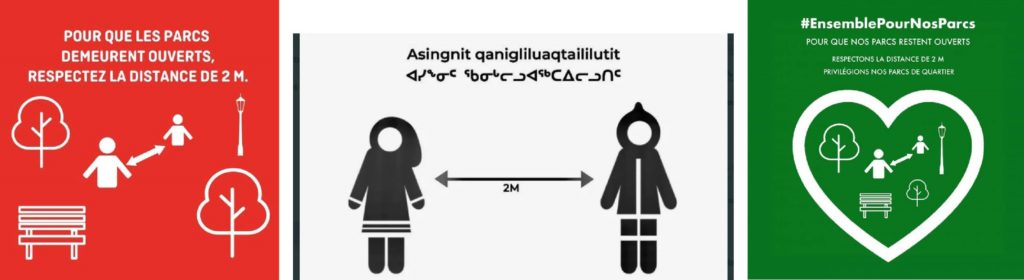

LEFT: An image shared on social media by Montreal Police Service and our mayor, Valerie Plante, kindly threatening the closing of parks if people do not respect the two-metre distance. The colour red is the official Montreal colour. CENTER: A poster produced by Inuit Tapiriit Kanatami tells Inuit, in Inuktitut and Inuinnaqtun, to respect the two-metre distance. As seen in a Godbout article on ici.radio-canada.ca. RIGHT: The image used by a grassroots campaign asking citizens to respect the two-metre distance for the sake of neighborhood parks. As seen on many websites, such as the Friends of the Mont-Royal park association.

For more than two weeks now in Montreal we have been expected to quarantine ourselves if we have any of the risk factors for COVID-19—principally arriving from out of country travel or likely exposure to others with the virus. Otherwise we must stay two metres from people we encounter on the street. Playgrounds and dog parks are closed, gatherings of more than 250 people are prohibited—that number has now shrunk to 2. The southernmost northern city is not built for such hard restrictions: Signs of spring are showing themselves, enticing Montrealers outside after long months of being cooped up against winter cold. Furthermore, most sidewalks are only 1.25 metres wide, which means that we cannot easily respect rules when crossing paths with strangers on our daily stroll. Those capable of it respectfully move onto the street—in normal times a life-risking proposition given the equally narrow streets and driving temperament of the typical Montrealer—while those with mobility limitations and encumbrances like us (I walk with a cane, my 6-year-old daughter is on her bike and my partner carries our 5-month-old) stick to the curb trying to stay grouped. Taking a walk outside becomes a fine dance of zigzagging between cars, avoiding contact, pretending everything is fine while keeping our guards up.

Back at home, I just finished a Skype meeting with the team of the Qanuikkat Siqinirmiut? How are the people in the south? project. We work on the much-needed understanding and definition of health for Inuit living in cities in the south of the Province of Québec. It is well established that people in Inuit Nunangat[2] suffer disproportionately from a range of chronic and communicable diseases that have largely emerged since the second world war following the sedentarization of Inuit into permanent communities in the Arctic by an expanding Canadian colonial state. While the conditions of Inuit health are relatively well described in the north, in contrast, we lack fundamental data to build services and programs that address their specific health conditions in the South; yet, while still small, the Inuit population living in the urban south increased by 76% between 2006 and 2011[3].

We are at the early stages of analysis, deeply immersed in the interviews we did with urban Inuit from all walks of life about their mental, physical, and social health: How are they feeling these days? What are they doing to stay healthy? What do they need to improve their conditions? During our discussions, a few interviewees mentioned not being in contact with their family because of their addictions. One Inuk would only be seen around Cabot Square, a popular gathering place and urban crossroads, when sober, and then would disappear from the public eye for a few days when using or drinking. Conversely, an Inuk woman we spoke with said she regularly spends a few days in downtown parks to use crack, away from her long-term partner who is sober and with whom she lives. Some mentioned not ever going back up north because of their addiction, making it difficult to travel, save money and keep up good relationships.

A few other people talk about going to great lengths avoid specific family members, friends or even whole neighborhoods (in the south) or villages (in the North). The reason? They themselves do not drink or do drugs, so they isolate themselves from their peers, friends, family members who do, sometimes putting 1,500 km between them. “I’m a very sober person and that’s why I’m thankful I’m here because I don’t have to be around my family who’s just drinking all the time.” In order words, they remove themselves from unhealthy environments. Socially isolating themselves in order to stay healthy in normal times is a heart-wrenching thing given the centrality of kin, visiting and conviviality in Inuit life.

Even though the restrictions imposed by the Canadian, Québec and local governments are very simple, the concept of isolation takes a different meaning in every household. We have seen, for example, calls for actions for the protection of women isolated at home with violent partners. Reflecting on the extraordinary situation imposed by the Covid-19 under the light of Inuit health strategies in the urban south, few considerations are emerging: the relative importance of family relationships to health, the time frame one gives oneself to act on one’s health (few days, a decade), the multiple symbolic values of city features like parks in health strategies (a leisure place for some, a drug supply source for others), the importance of power over one’s movements in the maintenance or improvement of health, the meaning of distance and how our environment supports or hinders a necessary distancing.

Hopefully, these considerations will help answer the main issue, which remains, for today and for better days, how to improve everyone’s health.

Nathalie Boucher

Directrice et chercheuse, organismerespire.com

Christopher Fletcher

Département de médecine sociale et préventive, Faculté de médecine, Université Laval

[1] Montreal, although a North-American city, looks up to Scandinavian countries for its urban planning; Meteorologically speaking, we qualify as a Northern city in the lines of Copenhagen and Oslo. But from the perspective of Inuit population living in the South, we could also consider Montreal as the Southernmost of the northern settlements.

[2] Inuit Nunangat: the four Inuit land claims regions (in northern Canada) of Nunavut, Inuvialuit Settlement Region (Northwest Territories), Nunatsiavut (Labrador), and Nunavik (Northern Québec)

[3] Tungasuvvingat Inuit. 2016. National Urban Inuit Strategy. Ottawa: Tungasuvvingat Inuit.